I recently received a message from a regular visitor asking how I was able to capture some specific images in Hong Kong that he’s been unsuccessful in replicating. When digging through my archives to find those images so that I could share the time of day, month and settings used, I had to confront a cold hard truth; the RAW images didn’t look even remotely close to the final images I posted online.

I had to confront a cold hard truth; the RAW images didn’t look even remotely close to the final images I posted online.

This got me thinking about where to draw the line on post processing and what the right balance is between showing the reality of a location (especially for a travel and photography blog) versus what the reality could be under ideal conditions. In this post, I’ll provide some examples of “before” and “after” and I’d love to hear your thoughts on whether I’ve gone too far, or not far enough.

Let’s first start with some principles I apply to any image, when determining if I’ve gone too far. I try to apply these principles when making the edits; the image should:

- 1. Convey a true representation of how I recall the scene appearing and feeling at the moment it was captured

- 2. Provide the viewer with a version that they could see with their own eyes under ideal conditions

- 3. Represent how people normally interact in that environment, without staging or using props

- 4. Show the subjects in a respectful way and ensure the main subject has provided verbal or written consent

- 5. Abide by all laws in the country in which it was taken

There are several more principles that can be applied, but these are the five that I run every image through before deciding to post them. We’ll go into each one in more detail and provide some examples along the way. It goes without saying that the most challenging one to balance is #2 because nobody wants to see a dreary image, but the post processing can quickly go from “making it a bit better” to “completely transforming the reality”.

1. Convey a true representation of how I recall the scene appearing and feeling at the moment it was captured

This principle is the easiest one to manage because it’s very subjective. This is where things like white balance come into play as I may recall the scene being warmer than the auto-white balance the camera chose. This can also be where Fujifilm’s excellent Film Simulations come into play to replicate how I felt at that moment. Fujifilm often talks about this “colour memory“.

There are times I’ve gone overboard and wish I had dialled it back a bit, but that’s part of the learning journey of photography.

With landscape images, they tend to look more lush and rich when viewed with my eyes than what I see on the screen, so I’ll tend to use the Astia or Velvia Film Simulations to boost saturation. There are times I’ve gone overboard and wish I had dialled it back a bit, but that’s part of the learning journey of photography.

I’ve heard it many times that photographers that look back at their original images from ten years ago, are typically aghast at what they thought looked good at that time. I tend to err on the side of caution and keep changes subdued from the heavily saturated look that’s so popular these days. I know that I give up some clicks and followers as a result, but I think it better matches Principle 1.

2. Provide the viewer with a version that they could see with their own eyes under ideal conditions

This is where problems start to appear and some judgement needs to come to the forefront. When the reader asked for the details on that particular image he’s trying to capture, you can imagine my surprise at seeing the unedited image below.

It had been some time since I took that image so I had forgotten how bad the actual scene looked. I know from having visited this spot many times that the image I posted can be obtained if you get ideal air conditions, however those perfect conditions come rarely in Hong Kong, with pollution and high humidity being two forces working against you.

Let’s look at another image where I perhaps went too far on the post production work; it’s a somewhat famous image now because David Grover at Capture One used it in one of his excellent tutorials. I say that I may have gone too far because I don’t live in Sri Lanka so I haven’t visited this spot often enough to know if it’s even possible to see the posted image with the naked eye, or if the conditions always are as it appears in the RAW image.

To this day, I don’t know if any of that’s true, and I hope that any travellers who make it to the top, do not leave disappointed at seeing a foggy Sigiriya Rock.

I took the liberty to make an assumption that the conditions could be much better, given that we saw beautiful blue skies around that location for several days leading up to the hike, and because some locals had told us we had bad luck with the air conditions on the that particular day. To this day, I don’t know if any of that’s true, and I hope that any travellers who make it to the top, do not leave disappointed at seeing a foggy Sigiriya Rock.

Flipping the tables around, Principle #2 is where I feel I’ve been burned the most in my travels. Many travel venues use very carefully composed images to portray the absolute best version of their location, without taking into consideration the disappointment felt by customers upon arriving at the destination; a room that looks massive in the image is actually much smaller in real life, or that the ocean view is actually only visible at certain angles that no human can achieve.

I don’t see anything wrong with these venues providing an ideal view of their property, but they should take into consideration what the human eye can see. Using an 8MM wide angle lens to make a room look larger is just setting people up for disappointment. Using a telephoto lens to show an ocean view makes little sense beyond providing a fraudulent expectation. Adding fake sunset skies to views from rooms facing the wrong direction is short term thinking and won’t fool anyone for long.

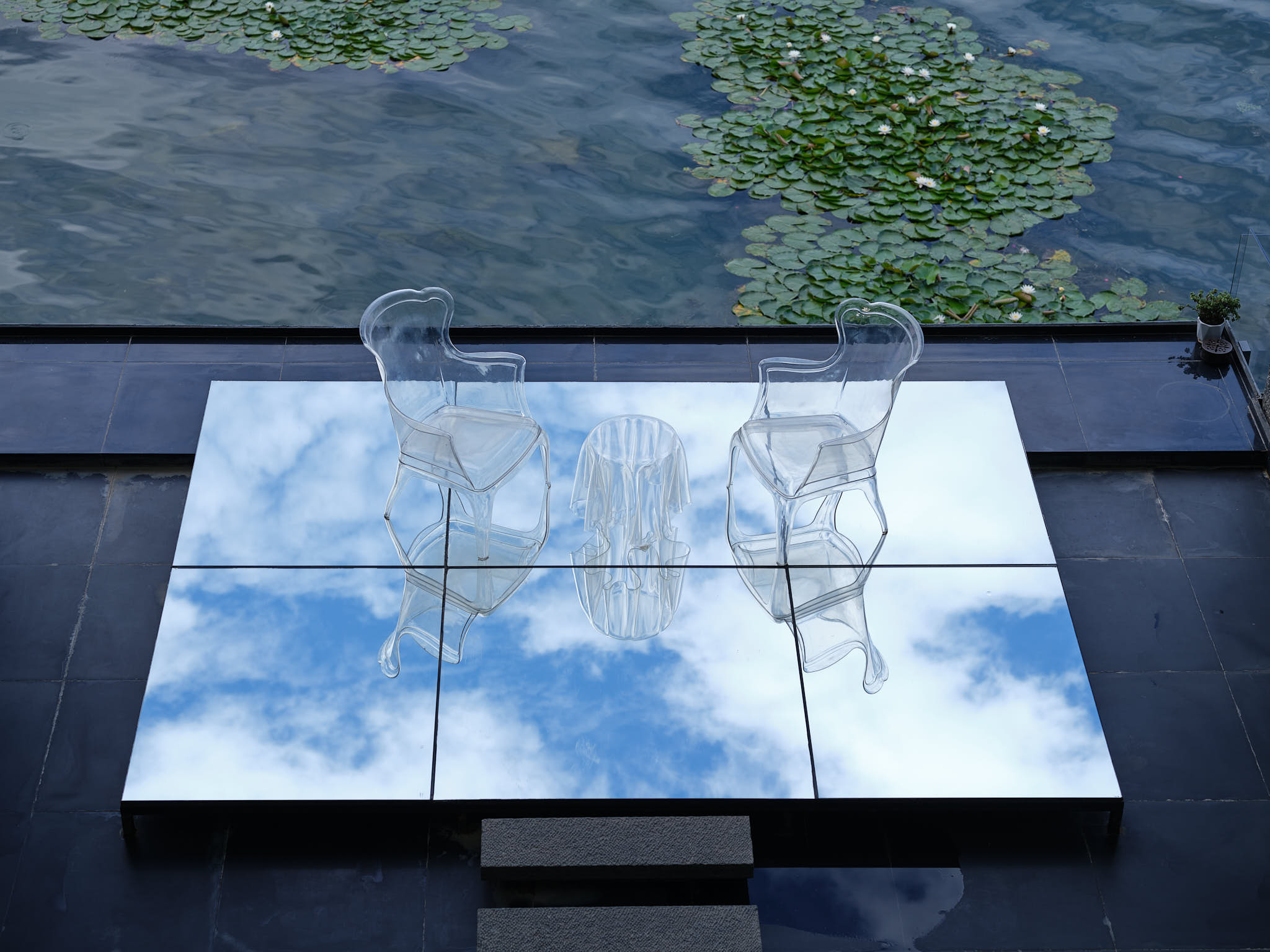

The above is an example of an image similar to what was prominently posted on a hotel’s website that shows a stunning scene in front of Erhai Lake. From the image, it gives the feeling of an expansive and relaxing area to have a glass of Prosecco or some white wine; at least that’s what my friends and I were thinking when we booked this hotel. The reality turned out to be quite different. There was nothing vast, nor relaxing about this spot, and we felt that the hotel and photographer had cheated us.

3. Represent how people normally interact in that environment, without staging or using props

This one is also tough to manage when trying to capture an environment that’s foreign to me, which by the nature of most tourism, is pretty much most images. By the very fact someone is pointing a camera at the environment, it will change the dynamic of the scene. I’m not doing photojournalism so I’m less concerned with that level of scrutiny, but I also don’t want to give the wrong impression of that location.

I’m not doing photojournalism so I’m less concerned with that level of scrutiny, but I also don’t want to give the wrong impression of that location.

I came across this thought recently when travelling to Kyoto, Japan. We had gone to Kinkaku-ji, a famous temple and taken an iconic image that every tourist wants to capture. My version appears to have no people in it and conveys the feeling of serenity. I knew when posting it that this was a stretch because the reality is that this spot is overwhelmed with tourists. To take that one shot, I had to plant my feet wide and take several images as people kept bumping me from behind.

I think for these types of images, nobody wants to see the beautiful temple with thousands of people in front of it. To adhere to the principle while also showing the beauty, I try to include additional commentary for context and to ensure the reader knows the reality so they’re not disappointed when they arrive to a swarm of thousands of iPhones and selfie stick wielding tourists (on another note, why are selfie sticks still a thing in 2020’s?).

4. Show the subjects in a respectful way and ensure the main subject has provided verbal or written consent

I feel a great amount of discomfort when I see pictures taken of homeless people or other subjects such as children when it doesn’t appear that the photographer has obtained the appropriate permissions. I can appreciate the power of an image and why someone would want to take that kind of image, but I forbid myself to post any image where I didn’t receive explicit (usually verbal) permission from the main subject or where the image represents the subject or subjects in a disrespectful way.

Asking for permission to take someone’s picture in a foreign environment can be a daunting experience, and in some parts of the world that means I won’t be getting many pictures of people during that trip; however, I think it’s the right thing to do to protect people’s privacy. I also never capture images of children unless accompanied with their parent and/or specifically with the parents permission.

Asking for permission to take someone’s picture in a foreign environment can be a daunting experience… however, I think it’s the right thing to do to protect people’s privacy.

There are also some situations where care needs to be taken in publishing images of groups; locations such as religious facilities or during religious ceremonies, images of women in some parts of the world, and of course children, all need to be carefully considered before posting an image.

I recall in Sri Lanka where a tourist was taking images using his mobile phone of monks observing sacred stone carvings inside a cave; the head monk was livid and knocked the phone out of the tourist’s hands. He then ensured every image was deleted and scolded the tourist in a fierce voice. Ask before taking I think is a good rule of thumb.

While there are many countries where people don’t like their picture taken, there are still billions of people that actually enjoy their pictures being taken. On my trip to India, there was an endless supply of amazing faces that were more than happy to be part of my photographic memories.

I found the same thing in Sri Lanka and in most South East Asian countries. Europe and North America however are different, where it’s becoming more and more unlikely that someone will say yes. Even here in China, it’s getting more difficult in the major cities as people prefer to protect their privacy; however, the smaller cities will find a receptive audience to your camera.

Even with permission, I think it’s also important to consider whether an image being posted is respectful to the people in the picture or the city and country the image represents. For example, it’s so easy when visiting a developing country to show only an underprivileged area to further the stereotype of that city or country.

It’s also important to consider whether an image being posted is respectful to the people in the picture or the city and country the image represents.

While it makes for a visually interesting image (especially for a western audience), it doesn’t often represent the reality of that city or country and the people living in it in our modern times. Heck, even my hometown of Vancouver can look markedly different if someone only takes pictures of the Downtown Eastside!

5. Abide by all laws in the country in which it was taken

With tensions rising between countries, this principle has taken on a whole new level of importance. I recall this issue arising on two trips. The first one was while on a trip to Sanya in southern China where our resort was located near a government navy facility.

As I was walking down to the beach with my GFX slung across my body, a soldier quickly approached and told me that my camera cannot be pointed west and that any images taken would result in immediate confiscation of the camera and memory cards, with the camera only being returned upon my scheduled return date. Needless to say, I did not take any sunset pictures from the beach on that trip!

As I was walking down to the beach with my GFX slung across my body, a solider quickly approached and told me that my camera cannot be pointed west and that any images taken would result in immediate confiscation of the camera and memory cards.

The second instance was in Sri Lanka. As we were walking around a nondescript area, our tour guide had what appeared to be a panic attack because we had inadvertently taken pictures of a government facility; I never did find out what facility it was since it didn’t appear on the map. He asked us to immediately delete the images (which were nothing worth saving anyways) and to quickly get out of the area before we attracted the wrong kind of attention.

This is also the reason I don’t take the DJI drone on travels. It’s a hassle to get the proper license for flying a drone in a foreign country, and even with a license, if you happen to accidentally capture a government or military facility, the punishment can be severe and difficult to overcome. I know of people that took drones to popular locations like Vietnam and ended up spending a few nights in jail because they accidentally took some innocent looking footage of secret facilities.

For anyone travelling to Asia that hasn’t been here in a while, I would recommend reading up on local laws and sensitive areas to ensure that you don’t end up in a sticky situation. The days of western tourists being given a pass for bad behaviour are mostly long gone. Some police forces actually relish the chance to dish out some local justice to the ill informed traveller. Your embassy will also not be able to help you, so it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Summary

To wrap up, I hope you’ve found the above interesting. I don’t think it’s an exhaustive list of principles or guidelines, so I would love to hear your thoughts. What else should we be considering when we take images of people, places or things? What has your experience been like when travelling and taking images, and how have you changed your approach over time? How do you determine if you’ve gone too far in the post processing such that the image no longer represents the reality?

Discover more from fcracer - Travel & Photography

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Your thoughts on post-processing are very similar to mine. I normally use the Provia simulation as a starting point. I find Velvia useful for landscapes, as somehow the other simulations don’t capture the impression we have of vivid green foliage. Astia is a good choice in the golden hour, as Provia doesn’t convey the impression of warm light very well. It also isn’t as extreme as Velvia.

Never mind. Working now.

Thanks for the heads up! I fixed it after you notified me 🙂

FYI: the before / after images with the sliders at the top of the page aren’t rendering in Safari or Chrome on the Mac nor iPhone. The regular images at the bottom seem fine.